When people talk about Dubai, they usually think of skyscrapers, luxury shopping, or desert safaris. But behind the glittering facade, there’s another layer of social life that rarely gets discussed openly-especially when it comes to the presence of foreign women working in companion services. Among them, Russian women are one of the most visible groups. They’re not here by accident. Their presence reflects deeper economic shifts, migration patterns, and the quiet realities of life in a city built on global mobility. Some come seeking better pay than they can find at home. Others are caught in systems they didn’t fully understand when they arrived. And yes, some are simply trying to survive in a place where the cost of living is high and the rules are strict.

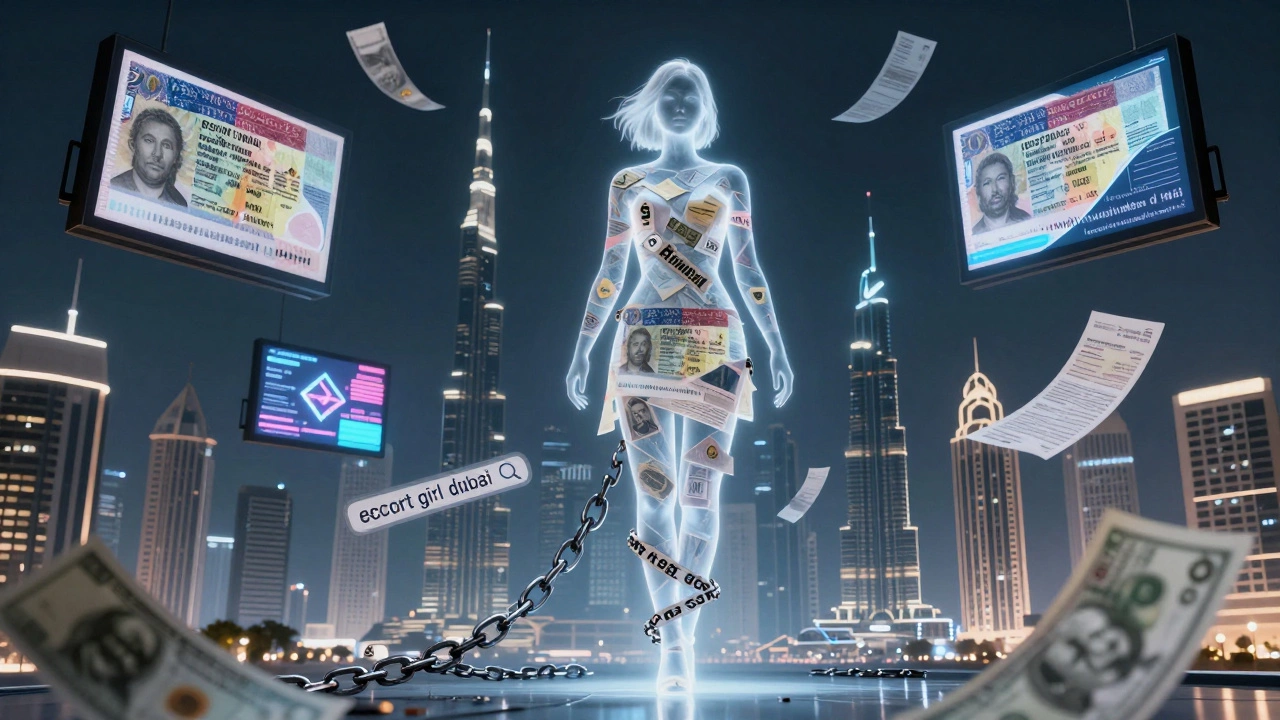

It’s easy to find ads online that use terms like escort girl dubaï, but these listings rarely tell the full story. Behind every profile is a person with a background, a reason, and often, a struggle. The language used in these ads-polished, professional, sometimes even glamorous-is designed to mask the vulnerability underneath. Many of these women speak multiple languages, have university degrees, or once held jobs in healthcare, education, or hospitality back in Russia. But after visa restrictions tightened, job markets collapsed, or personal circumstances changed, they found themselves in Dubai with few legal options.

Why Russian Women in Dubai?

Russia has seen a steady outflow of women seeking work abroad since the early 2010s. Economic instability, wage gaps, and limited upward mobility pushed many toward countries with higher earning potential. Dubai, with its tax-free income and demand for service workers, became a magnet. Unlike other Gulf cities, Dubai doesn’t require foreign workers to have a local sponsor for every type of visa. That loophole-though technically illegal for certain activities-has been exploited for years. Many Russian women enter on tourist or visit visas, then extend their stay through informal networks. Some work in hotels, spas, or modeling agencies. Others transition into companion services because the pay is higher and the hours more flexible.

The numbers aren’t officially tracked, but local law enforcement and NGOs estimate that thousands of Russian women live in Dubai under informal arrangements. Most don’t identify themselves as sex workers. They prefer terms like “companion,” “hostess,” or “model.” The distinction matters-it’s about perception, safety, and legal risk. In Dubai, prostitution is illegal. So is soliciting. But the line between companionship and sexual services is blurry, and enforcement is inconsistent. What’s clear is that the demand exists, and supply follows.

The Role of Language and Culture

Russian women often stand out in Dubai’s service scene because of their language skills. Many speak fluent English, some French, and a few even Arabic. That’s not common among all foreign workers here. Their cultural background also plays a role. Russian women are often perceived as more direct, confident, and emotionally expressive than women from other regions. That can be attractive to clients who want someone who doesn’t play games or hide intentions. But it also makes them targets. They’re more likely to be approached, more likely to be scammed, and more likely to be reported by jealous rivals or disgruntled employers.

There’s also a cultural myth that Russian women are more “open-minded” or “easy.” That stereotype is dangerous and false. Many are deeply religious, family-oriented, or traumatized by their experiences. They don’t fit the cliché. And yet, that image is what drives demand. Ads use phrases like “Russian beauty with European manners” or “educated escort a dubai” to appeal to specific tastes. These aren’t just marketing lines-they’re tools that reduce real people to marketable traits.

Legal Risks and Social Isolation

Dubai’s legal system is unforgiving when it comes to morality-related offenses. A single arrest for solicitation can lead to detention, deportation, and a permanent ban from entering the UAE. Many women don’t realize this until it’s too late. They’re told by recruiters that “everyone does it,” or that “the police don’t bother foreigners.” That’s not true. In 2023, over 120 foreign women were deported from Dubai for violating visa terms related to companionship work. Nearly half were Russian nationals.

Once arrested, they lose everything: their passport, their savings, their housing. Some are held in detention centers for months while paperwork drags on. Others are handed over to consulates that offer little help. There’s no support system. No counseling. No job retraining. Many end up back in Russia with no way to explain what happened, or worse, with no one to return to.

Outside the legal system, social isolation is just as damaging. Most live alone in small apartments in areas like Jumeirah, Marina, or Discovery Gardens. They don’t have friends. They don’t trust neighbors. They avoid public spaces. Their only real connections are with other women in the same situation-or with clients. That kind of loneliness eats at mental health. Depression, anxiety, and substance abuse are common but rarely discussed.

Who Are the Clients?

The assumption is that clients are wealthy expats or tourists. That’s partly true. But many are local Emiratis-men who can’t openly date or marry foreign women due to cultural norms. Others are middle-class professionals from India, Pakistan, or the Philippines who earn decent salaries but have no access to romantic relationships in a conservative society. There’s also a surprising number of older men, widowers, or divorced fathers who crave companionship without the complications of emotional intimacy.

What’s rarely acknowledged is how much of this work is transactional loneliness. The clients aren’t always looking for sex. Sometimes they just want someone to talk to, to eat dinner with, to feel normal around. The women know this. Many of them spend more time listening than anything else. They become therapists, confidantes, and emotional buffers for men who have no one else to turn to. That’s not in the ads. That’s not what the headlines say. But it’s real.

The Myth of Choice

Some argue that these women chose this path. That they’re empowered. That they’re in control. That’s a comforting narrative, but it’s not always true. Choice requires alternatives. For many, there are none. A woman from Volgograd who lost her job in a factory and can’t afford rent back home doesn’t have a lot of options. A mother in Rostov who needs to send money to her child’s school doesn’t get to pick between dignity and survival. The idea of “choice” only exists when you have safety nets. For these women, there are none.

Even those who seem to be in control-those who set their own rates, choose their clients, and work independently-are still operating in a system designed to exploit them. The platforms they use, the agencies that connect them, the landlords who rent to them-all take a cut. The system is built to profit from their vulnerability, not uplift them.

What About Other Nationalities?

Russian women aren’t the only group. There are also Ukrainian, Moldovan, Romanian, and Brazilian women. But they’re not the only ones. You’ll find escort algérienne refers to women from Algeria working in companion services in Dubai, often entering on tourist visas and navigating similar legal and social risks-a smaller but growing presence. Some come from North Africa seeking work after the economic downturns in their home countries. Their stories are even less visible. They speak less English. They have fewer networks. They’re more likely to be ignored by media and aid organizations alike.

There’s also a quiet presence of women from Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe who work under different labels-nannies, tutors, or personal assistants. But when the line between domestic work and companionship blurs, the same risks apply. The system doesn’t care about your job title. It cares about your visa status, your nationality, and whether you’re alone.

Where Do We Go From Here?

There’s no easy solution. Criminalizing these women doesn’t help. Ignoring them doesn’t help either. What’s needed is a shift in how we talk about this issue. Instead of sensationalizing it or moralizing it, we need to see these women as people-not as problems, not as symbols, not as content for voyeuristic blogs.

Some NGOs in Dubai are quietly starting support programs: legal aid for deported women, language classes for those trying to transition out of the industry, mental health counseling. But they’re underfunded and operate in the shadows. The government doesn’t fund them. The media doesn’t cover them. The public doesn’t know they exist.

Real change would mean reforming visa policies to allow legal work for foreign women in non-exploitative roles. It would mean creating safe housing options. It would mean teaching employers not to assume that foreign women are “available.” It would mean treating them as human beings with rights-not as commodities.

For now, the system continues. Women keep arriving. Clients keep calling. Ads keep running. And somewhere, a woman in a quiet apartment is wondering if tomorrow will be better than today.

It’s not about judgment. It’s about recognition. These women are part of Dubai’s hidden economy. And until we acknowledge that, nothing will change.

Some online listings still use phrases like escort a dubai a commonly used search term in informal networks to describe foreign women offering companionship services in Dubai, often linked to visa violations and economic pressure. Others use escort girl dubaï a French-influenced spelling used in multilingual ads targeting European clients, often masking the legal risks faced by the women behind the profiles. These aren’t just keywords-they’re echoes of real lives.